Is there such a thing as too clean?

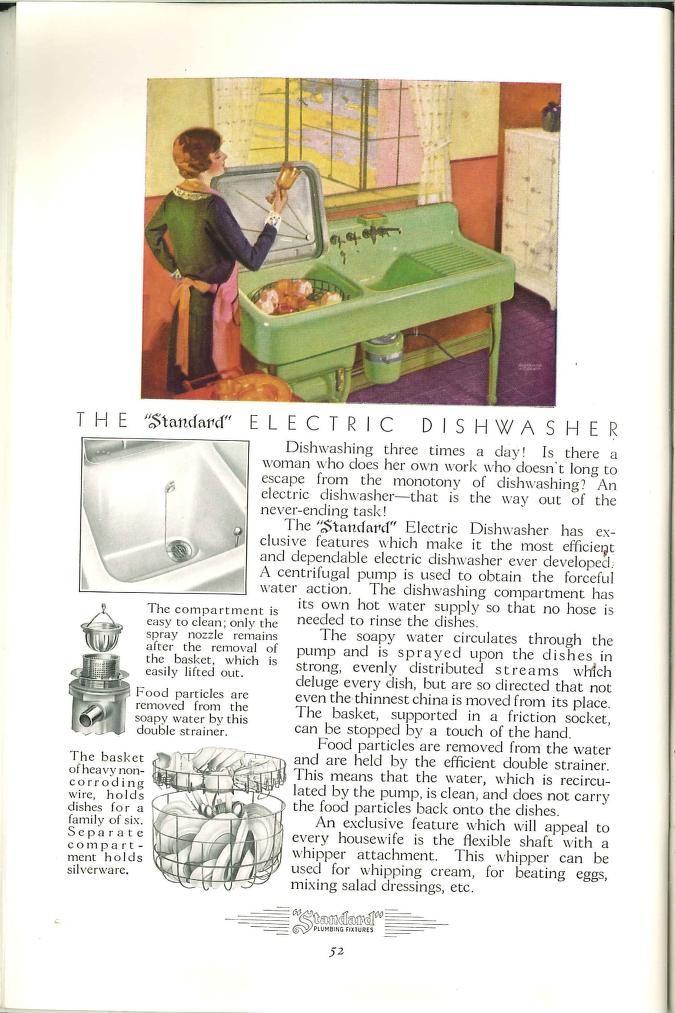

‘Standard Plumbing Fixtures for the Home’, Standard Sanitary Manufacturing Company (1930)

In the fall of 2021, a few things converged to make me think about cleanliness as a historically specific practice. As the parent of a young child I was in a constant struggle to keep things clean. Soaking foodstained shirts in oxygen bleach or scrubbing them with stain removers, I wondered about the environmental calculus of cleaning clothes. My cleaning certainly kept the clothes in circulation longer. But it also sent chemicals down the drain, and left a trail of empty plastic bottles. Meanwhile, at that stage in the COVID cycle, we were learning that our first impulse to bleach, wash, and sanitize all surfaces had ultimately made little to no difference in the spread of this airborne disease. Finally, I was discovering that many skin troubles such as eczema are improved by washing skin less often, using less soap or none at all. It seemed as though our rituals of cleanliness might not be serving us very well, and they certainly were not doing our water, soil, or air much good.

As a result, I have launched a new research project, a history of ‘clean’ in the twentieth-century United States. U.S. history is my field of expertise and, handily, Americans turn out to have been innovators and early adopters of many cleaning practices that British readers will recognize. I am focusing on the home, while also looking outwards at institutions, such as the laundromat, and people, such as hired cleaners, that helped Americans keep clean.

Across the twentieth century, the labour of cleaning has changed less than one might expect. Machines made it possible for a family to keep themselves and their home clean without hiring others to help them. These “labour-saving” devices allowed many Americans to enjoy clean sheets and clean carpets, but they did not really decrease the number of hours that people spent cleaning. Meanwhile, alternatives to the isolation and inefficiencies of the single-household model—whether outsourcing, centralizing, or collectivizing labour—rarely took off.

A dramatic environmental change took place with less fanfare, as synthetic materials came to do the lion’s share of Americans’ cleaning. Made from petroleum rather than vegetable or animal fats, synthetic detergents took off in the 1950s, and most people have never looked back. Synthetic soaps often included synthetic smells. Eventually air fresheners, “scent boosters,” and Febreeze trained people to associate strong smells, rather than the absence of smell, with cleanliness.

The environmental and health effects of our cleanliness regimes will be the most difficult research task within this project. Corporations were rarely asked to account for the environmental or health outcomes of their products, except for the most toxic. This means scientists and ecologists were always only catching up with damage already done, and they could measure but a part of it. Still, I can draw upon strong evidence when discussing the effects of Triclosan (a common antibacterial ingredient) in the human body, perchloroethylene (used for dry cleaning) on air quality, and phosphates (in laundry detergent) in rivers and lakes.

My goal is not to minimize the difference that clean water, indoor plumbing, or hand washing has made to the health and life expectancy of Americans in the twentieth century. Instead, I hope to take full account of the tradeoffs that Americans have made in their pursuit of cleanliness, and to notice how the meaning of cleanliness itself has changed over time. With allergies on the rise, plastics accumulating in our oceans, and toxic algae blooming in phosphate-rich runoff, it is becoming clear that there is such a thing as too clean.

Julia Guarneri is an Associate Professor of American History