Alumni perspectives: Leo Sands

Leo Sands compares the History Tripos and journalism

A few days after exams finished in 2016, I recoiled in horror at the sight of my dad sparring over Brexit with a random person’s parents at my college’s graduation lunch. In Cindies, a fight broke out between someone waving an EU flag and a rival group trying to set it alight. The referendum vote, scheduled for the following week, cast a tense shadow over May Week.

One morning a few months on, in a seminar hosted by Gary Gerstle for graduate students of American history, we sat in silence, reflecting on the moment. Donald Trump had just won the US election and it was clear that history was not finished with us.

The political earthquakes of 2016 coincided with when decisions had to be made on what to do next, and I wonder if it explains why so many of my friends decided to try journalism.

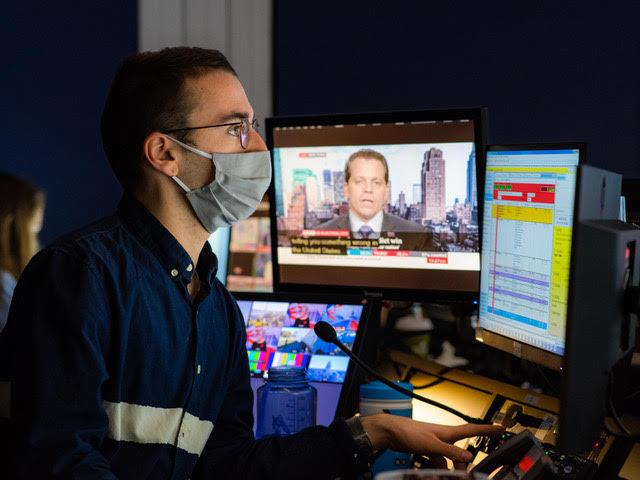

After freelancing as a BBC researcher, I picked up some shifts as a television producer in a whole variety of BBC departments – the politics team, a year in Wales on a live debate show, and eventually at the rolling news channel where I worked for four years as a television producer, before switching to the website as a news writer. Lots of people start their newsroom careers that way – beginning with the odd shift and ending up with a full-time job.

A great thing about journalism is that if you have a good idea, no matter your role, the right editor might let you roll with it. After I heard an insane story about a Covid working-from-home con, I ended up producing a TV documentary for BBC Three (Jobfished) investigating who could have been behind it. My BBC highlight was in Washington though, producing live TV coverage of the 2020 US election results. By pure chance, I was the producer in situ when the BBC called the election for Biden, making it my job to tell the presenter to declare the race.

Since 2022, I’ve been a reporter and editor at The Washington Post, based in the paper’s London breaking news hub. In many ways, it couldn’t be more similar than the job of a historian. Your task is to assess sources for reliability, speak to the people involved in big (or small) events – trying to get as close to a verifiable first-hand account as possible. You then pit the different versions of events against one another to see what stacks up, as open-mindedly as possible, with the hope of distilling meaning from the chaos.

Similarities between journalism and the history tripos: Lots of writing; treating big claims with sceptical open-mindedness; filing a breaking news story to deadline is a lot like churning out a finals essay.

Differences: Most deadlines are measured in minutes or hours, not days or weeks; you need to cut to the chase asap, ideally in the first sentence; most of the people you need to speak to are still alive.