MPhil in World History

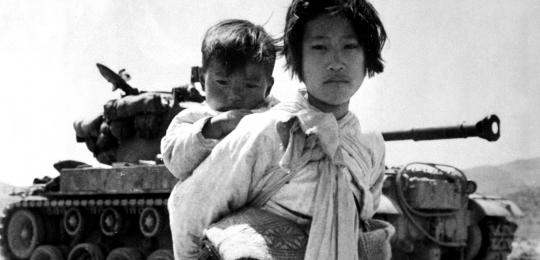

Visit to the Departures exhibition organised by The Barakat Trust and Asia House

Overview

World History at the University of Cambridge combines the study of global and imperial history with the study of Asian, African, Latin American and Pacific histories. It draws upon the expertise of faculty members in each of these areas, as well as in Middle Eastern, Oceanic and American history. The MPhil in World History enables students to develop strong expertise in this rich and expanding field of historical scholarship.

The MPhil in World History combines courses and a dissertation over a 9-month program. The core course focuses on historiographical debates in world history, leading to two options, usually in the history of a world region. From the first term, students also begin directed research for a 15,000 word dissertation, working closely with their supervisor from the Faculty’s World History Subject Group. Students will also take language classes, a component that is required but not examined. This may be in any language offered by the Cambridge University Language Centre, and may be elementary, continuing or advanced. In this way, the MPhil in World History offers students thorough preparation for an advanced research degree that will be highly valued in institutions across the world.

At a glance

All students will submit a thesis of 15,000–20,000 words, worth 70 per cent toward the final degree.

Students also produce three 3,000-4,000-word essays, two in Michaelmas term and another in Lent term; each essay is worth 10% of the final degree grade.

All students admitted to the MPhil in World History will be assigned a supervisor to work with them throughout the course, but crucially on the dissertation. Students will meet regularly with their supervisor throughout the course.

Students can expect to receive:

- regular oral feedback from their supervisor, as well as termly online feedback reports;

- written feedback on essays and assessments and an opportunity to present their work;

- oral feedback from peers during graduate workshops and seminars;

- written and oral feedback on dissertation proposal essay to be discussed with their supervisor; and

- formal written feedback from two examiners after examination of a dissertation.

If you have any questions, drop us a line on world@hist.cam.ac.uk

Aims of the Course

The MPhil in World History aims to:

- Explore why world history is one of the fastest growing fields of research in current historiography, and how post-colonialism, trans-nationalism and their revisions have driven this burgeoning literature;

- Train students in the use of the printed, manuscript, visual and oral sources for the study of world history, and introduce the use of sources, within and beyond the colonial and national archives;

- Offer an intensive introduction to research methodologies and skills useful for the study of world history, including language skills;

- Introduce new regions, perspectives, connectivities and ruptures in historical processes in their widest extent, and in local, continental or oceanic settings; and

- Provide an opportunity for students to undertake, at postgraduate level, a piece of original historical research in world history under close supervision: to write a substantial piece of history in the form of a dissertation with full scholarly apparatus.

By the end of the programme, students will have:

- Knowledge of key debates and trends in world history and historiography;

- Skills in presenting work in both oral and written form; and

- Acquired the ability to situate their own research findings within the context of previous and current interpretative scholarly debates in the field.

The Course

Core Course: Debates in World History

Under what circumstances did the scholarly field of world history emerge? How do its concerns overlap with, and differ from, those of global and imperial history, area studies, and post-colonial studies? This core course for the MPhil in World History provides an overview of key historiographical debates, through close reading of significant interventions in the secondary literature. It is taught through a series of eight two-hour discussion seminars, in which students will participate actively. The course will be run jointly, and members of the World History group will take specific sessions on fields in which they specialise.

Topics for 2023-24:

- Imperialism, colonialism, post-colonialism

- Gender and world history

- Global intellectual history

- Economic history and world history

- Race and racism in world history

- Local and global approaches to religion

- Deep history and environmental history

There are five components to the MPhil in World History:

- core course

- first option

- second option

- dissertation

- language

Core Course

- Debates in World History (weekly seminar x 8 weeks)

Option 1

- weekly seminar x 8 weeks

Dissertation research and supervision

Language

- 1 session per week

Applying to the course

To apply to the MPhil in World History, you will need to consult the relevant pages on the Postgraduate Admissions website (click below).

Since applications are considered on a rolling basis, you are strongly advised to apply as early in the cycle as possible.

On the Postgraduate Admissions website, you will find an overview of the course structure and requirements, a funding calculator and a link to the online Applicant Portal. Your application will need to include two academic references, a transcript, a CV/ resume, evidence of competence in English, a personal development questionnaire, two samples of work and a research proposal.

Research proposals are 600–1,000 words in length and should include the following: a simple and descriptive title for the proposed research; a rationale for the research; a brief historiographic context; and an indication of the sources likely to be used. The document should be entitled ‘Statement of Intended Research’. Applicants are encouraged to nominate a preferred supervisor, and are invited to contact members of the Faculty in advance of submitting their application to discuss their project (see our Academic Directory: https://www.hist.cam.ac.uk/directory/academic-staff).

Below are some anonymised examples of research proposals, submitted by successful applicants to the MPhil in World History. You may use these to inform the structure of your submission. Please note that they are purely for guidance and not a strict representation of what is required.

World History - Research Proposal 1

World History - Research Proposal 2

Assessment & Dissertation

Part I

Each of three modules in Michaelmas and Lent (one Compulsory Core, and two Options) will require a 3,000-4,000 words essay (or equivalent). Each will count toward 10% of the final degree mark, for a total of 30%. Taken together, these are Part I, and students must receive passing marks in order to move to Part II.

Students will also prepare a 2,000 word dissertation proposal essay due in the Lent Term. This essay will be unassessed but students will meet with their supervisor to discuss the essay and get feedback.

Part II

The Dissertation or Thesis is Part II of the course. Each student on the MPhil will prepare a thesis of 15,000-20,000 words.The thesis will be due in early-June and will count for 70% of the final degree mark.

An oral examination will only be required in cases where one of the marks is a marginal fail.

The Dissertation, or thesis, is the largest element of the course, worth 70% of the final mark.

Students are admitted to the University on the basis of the research proposal, and each student will be assigned a Supervisor who will support the preparation of a piece of original academic research. Candidates must demonstrate that they can present a coherent historical argument based upon a secure knowledge and understanding of primary sources, and they will be expected to place their research findings within the existing historiography of the field within which their subject lies.

All students should be warned that thesis supervisors are concerned to advise students in their studies, not to direct them. Students must accept responsibility for their own research activity and candidacy for a degree. Postgraduate work demands a high degree of self-discipline and organisation. Students are expected to take full responsibility for producing the required course work and thesis to the deadlines specified under the timetable for submission.