Religious Minorities and National Identity in Southern Ireland Since 1912

The Project.

What was the role played by religious minorities in the transformation of independent Ireland from a conservative, ‘monocultural’ society, to one apparently at ease with a pluralist identity? What is the relationship between the old minorities (Protestants and Jews), ‘left behind’ at the end of the Anglo-Irish Union in 1922, and those which have emerged in recent decades, through large-scale immigration, including Muslims and Eastern Europeans? Exploring these questions from the point of view of the minorities themselves, this project provides the first inclusive history of groups on the margins of traditional Irishness. It shows how confessional and social distinctiveness was preserved, and examines the role of diversity in reconfiguring national identity and stimulating innovation.

My project is about how minorities defined themselves in relation to both the ‘majority’ and other minority groups, and how they responded to changes in the wider world – to which they were intimately connected through personal, social and religious links. It does so by listening to their narratives, and recreates a world view which amounted to an alternative history of Ireland – one written from the point of view of those who were at the margins of Irish legitimacy in the official, nationalist narrative, but did not fit in the parallel Ulster Unionist account.

The project’s explanatory strategy links 21st-century pluralism (and its limits) to the constitutional and cultural framework which in the first part of the 20th century helped to manage the ethno-diversity inherited from the British Empire. Thus, my main argument is that dealing with diversity substantially contributed to Ireland's social capital. Exposure to minority dissent enhanced both public debates and individual choices, and contributed to the country’s ability to take in new inputs and think about them more creatively. Methodologically, this research is comparative, based on the conviction that Ireland is best understood in its wider context, and that, in turn, Irish history helps us to appreciate better problems of general relevance in European history.

I have split the project into two parts: the first focuses on the period between 1912-66, when Ireland took shape as a confessional democracy, dominated by ideas of popular (in contrast to parliamentary) sovereignty. Though it was a period of revolution and change, it was also dominated by one main issue – how to forge a democratic nation-state out of the debris of the United Kingdom, and how to reconcile the ‘general will’ with liberalism and diversity. The second part will focus on the period since 1966, which was also characterised by rapid change, including reactions to the Northern Irish Troubles, the impact of both Vatican II and the child abuse scandals on the Catholic Church, unprecedented economic growth, and the mass immigration from the 1990s, which transformed the republic into a multi-cultural society.

1912-1967.

One hundred years ago most of Ireland ceased to be part of the United Kingdom and became the Irish Free State, encompassing 26 of the island’s 32 counties. The remaining Six elected to stay closely associated with Britain as the self-governing province of Northern Ireland. Partition was ultimately about one issue: minorities, their oppression (real or imagined, anticipated or remembered), their rights and demands and the way such demands might be reconciled with the nation’s territorial integrity.

Like in Central and Eastern Europe, democracy in Ireland sat on the horns of a dilemma: for, while partition was perceived as ‘the only way to … protect minorities and majorities’, in order to allow the latter to govern and democracy to work, marginalising minorities raised questions ‘about justice - a contest over who should belong, could belong [and] deserved to belong’. 1. Because it was impossible to draw state boundaries without further splitting up communities, each of the two Irish jurisdictions carved up minorities, imprisoned in a state which claimed to be national, but was not the nation of their choice.

As in most other parts of the world at the time, it was religion that defined ‘minorities’ and ‘majorities’, shaping their culture, historical memory, family networks, public perceptions, political orientation and social connections. Minorities in the Irish Free State consisted primarily of Protestants and Jews and, in the inter-war world, stood out for three reasons. First, unlike the Catholic Nationalists in Northern Ireland, they were too small to contest the post-imperial settlement: in other words, they held no irredentist hopes and accepted that they were minorities. Second, they were largely ‘privileged’ groups and were recognized as such by the state, for example in the 1937 constitution. And third, the polity within which they were ‘imprisoned’ was a far more stable democracy than most of the other post-imperial states in inter-war Europe.

Most existing studies of these groups focus on how the new state affected them. By contrast, my research is more interested in the question whether minorities contributed to democratic development in Catholic Ireland. The answer it proposes is that they did, but largely because they had been neutralized. They were minimized in numbers, thus fulfilling what Tomas Masaryk described (in 1918) as the precondition for toleration. 2. Furthermore, they were subjugated, in the sense described by Kalyvas, i.e. ‘made to know that they [were] not only powerless, but that any desperate attempt to make trouble ... [would] only bring upon them certain destruction’. 3.

British Gendarmerie officers in Palestine ca 1924: most of them were former Black & Tans and Royal Irish Constabulary men, forced to flee Ireland after the Revolution.

The draft chapters which I have written so far start by exploring the devastating impact of ‘popular sovereignty’ on the delicate ethnic balance in Ireland, the impact of revolution and civil war in 1916-23, and the search for normality in the 1920s. They examine various spheres of community life and minority self-representation. Protestants tended to develop attitudes and survival strategies similar to those which generations of Rabbis had for centuries recommended to diasporic Jews: they needed to accept their liminal status, display patriotism, and make themselves useful by specialising on the provision of services (such as insurance, banking and manufacturing). At the same time, for both groups religion became a substitute for politics. In Dublin, the Jewish Chief Rabbi, Isaac Herzog, elaborated what I describe as a ‘theology of exile’ and encouraged Zionism. While some of his community started to ‘make Aliya’, Protestants too did the equivalent in their own way: more than 36% of them had left independent Ireland by 1926. Hundreds of former police officers actually went to serve in the British police in the Middle East, thus creating an interesting cultural experiment: partitioned Ireland garrisoning an as-yet unpartitioned Palestine.

Rabbi Isaac Herzog, Ashkenzi Chief Rabbi of Palestine, delivers an addresses a Zionist rally at the Neu Freimann displaced persons camp, ca 1946. He had been the Chief Rabbi of Ireland until 1936. Supposedly close to the Irish Revolution, was actually much more ambiguous in his view of the Union and the British Empire.

Among the Protestant metropolitan elite, industrialists and bankers continued to operate in an ideally-unpartitioned British Empire world, while theologians and journalists embraced the ‘social gospel’ and the League of Nations as their new mission to the Irish. For groups who feared persecution and were not comfortable with an exclusive allegiance to Éire, internationalism was more than an ideal – it was a plausible alternative to both claustrophobic nationalism and sectarianism, a way of claiming the high moral ground in a world which they could no longer control. Minority internationalism was like ‘keeping a window open towards Jerusalem’, like exiles searching for a spiritual ‘promised land’. The metaphor was frequently used among minorities in post-revolutionary Ireland. The related attitude were compatible with the minority practice of keeping a low profile in domestic affairs, while claiming a higher allegiance to transnational concerns and connections, including the British Empire and the Jewish settlements in Mandate Palestine. The latter was a lively concern in Dublin, partly because Irish Jews played an important role in early Zionism, especially from 1936, when Herzog was appointed Chief Rabbi of the Holy Land, and partly because Southern Irish Protestants played an important part in garrisoning the Mandate until 1948.

The autumn will be devoted to revising these draft chapters and writing two more – covering, respectively, the 1940s and the 1950s and early 1960s. Meanwhile, the Leverhulme Trust has granted permission to reallocate part of the funds originally destined to research trips – which had to be cancelled since the outbreak of Covid in March – to paying for a Research Assistant. I was fortunate enough to find a passionate co-worker in Charles Francombe, who completed his M.Phil. in June. As my RA, Charles is analysing the online records of the Irish Freemasons, an important and understudied primary source. This in turn has revealed and opened up new perspectives and opportunities in the study of global Irish business networks.

One exciting dimension of this research was securing access to several manuscript collections in private archives which had seldom or never before been examined by scholars. Of these, two are particularly extensive and significant. One is the Whitla-Lucas-Thompson Archive, documenting the social and cultural life of a distinguished aristocratic family from Co. Cork and Co. Meath. This encompasses a wide range of materials, including letters, ephemera and and the diaries of Violet and Betty Whitla-Lucas, mother and daughter, which cover most of the time between the First World War and the end of the 1970s. 4.

Violet Mackay and Fredric Whitla-Lucas’ wedding day, 1911. © P. Conlan.

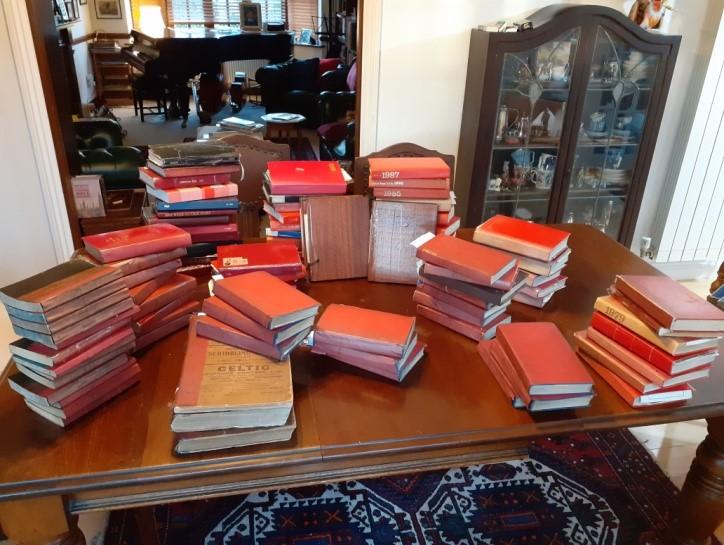

The Arthur Bateman Diaries 1948-2009.

The second are the diaries of Arthur Bateman. He was a Dublin journalist with the Irish Times, a Reader (lay preacher) in the Church of Ireland, and the son of Canon Eric Bateman, whose collection of sermons represent the most systematic and detailed Protestant religious commentary on Irish affairs from 1916 to 1979. While Eric Bateman’s papers are preserved in the Church of Ireland Archives in Dublin, his son’s manuscripts are in the possession of his nephew, Bishop David Chillingworth, former Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church.

He and his family graciously allowed me not only to consult the diaries, but also to store them for the duration of the project (I shall need the family's written permission in order to cite or quote from these papers). The Arthur Bateman diaries cover 61 years (1948-2009), recording, in the most minute details, daily life, national events and changing minority perceptions of themselves and the wider world. They comprise dozens of handwritten volumes perhaps amounting to about 11,000,000 words.

Both collections are very significant, representing two of the most important sets of ‘self-writing’ in modern Irish history, in some ways comparable to the diaries and papers of the Quaker Rosamond Jacob (deposited in the National Library of Ireland. See here for the collection catalogue).

While the extent and ambition of a study on elite minorities at the end of empire is global and potentially endless, I plan to have a book manuscript ready for submission by the end of the Michaelmas Term, though this will cover only the first part of the period which I study – namely from 1912 to ca. 1965.

References.

1. S. Monaghan, Protecting democracy from dissent: population engineering in Western Europe 1918-1926 (London, 2018), 42, 126 and 210.

2. T. Masaryk, The New Europe (the Slav standpoint) (London, 1918), 84.

3. S. N. Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War (Cambridge, 2006), 150.

4. These papers have been partly explored in Anna Christina Conlan, ‘The Whitla-Lucas archive. Exploring the personal within feminist scholarship and questioning desire in women’s life-writing’, Feminist Theory, vol. 5(3): 257–279. 1464–7001, DOI: 10.1177/1464700104040812