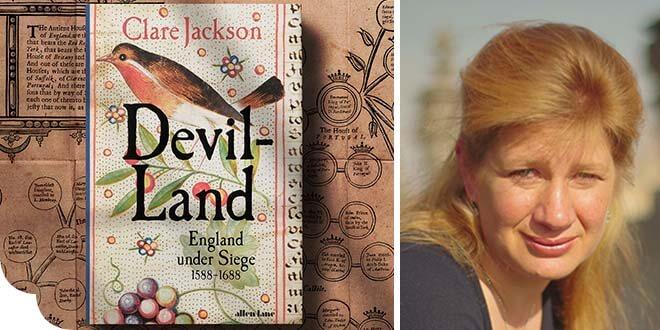

Devil-Land. England under Siege 1588-1688

Clare Jackson

By coincidence, I signed the contract with Penguin to write Devil-Land. England under Siege 1588-1688 in the week that followed the referendum held on 23 June 2016 in which a majority of the United Kingdom’s electorate voted to leave the European Union. I finished the manuscript in the week after the UK’s final departure from the EU, following expiry of the ‘transition period’ on 31 December 2020. Amid a new coronavirus lockdown, France had shut its borders to the UK, and miles of queueing Continental hauliers were stranded in Kent. Written in the shadow of Brexit speculation and debate, Devil-Land’s focus on the contingent mutability of seventeenth-century England’s relations with its Continental neighbours provides perspective, if scant comfort, for its readers.

Devil-Land’s title derives from the nickname ‘Duyvel-Landt’, coined by an anonymous Dutch pamphleteer in 1652. Reversing familiar Latin puns whereby the English (‘Angli’) were to be cherished as cherubic angels (‘angeli’), the English appeared, rather, as diabolically dreadful king-killers. Three years earlier, the English had sent shockwaves throughout Continental Europe by putting their divinely ordained king, Charles I, on trial for high treason and executing him in public. Defiantly unrepentant, the new republican regime’s leaders in London were now about to declare war on their fellow Protestant republicans, the Dutch, in the first of a series of seventeenth-century Anglo-Dutch wars fought over trade routes and colonial expansion.

Dissecting a nation’s endemic fears, anxieties and insecurities, Devil-Land’s account is bookended by two foreign invasion attempts. It opens in the late years of Elizabeth I’s reign which saw a vast Spanish fleet, comprising over 130 ships, 7,000 sailors, 17,000 soldiers and around 1,300 officials enter the English Channel in August 1588, hoping to rendezvous with Philip II of Spain’s nephew, Alexander Farnese, duke of Parma, who would bring an invasion force of 27,000 Habsburg soldiers across from Flanders to land in Kent. Spanish ambitions were frustrated by summer storms and poor communications, and the scattered Armada embarked on a circuitous return journey via northern Scotland, western Ireland and the Bay of Biscay, during which a third of its ships sank, and over half of its sailors and soldiers drowned or died from starvation or being lynched on beaches. Devil-Land concludes its account, a century later, with another foreign seaborn invasion that did succeed: when William of Orange’s force of around 400 ships, 15,000 soldiers and 3,000-4,000 horses landed at Torbay in Devon on 5 November 1688, prompting his Catholic uncle and father-in-law, King James VII & II, to flee to Louis XIV’s France.

Inspiration for Devil-Land’s arguments came from five television films I made for the BBC entitled The Stuarts and The Stuarts in Exile in 2014-15. Commissioned in the run-up to the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, the films revisited the Stuart rulers of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales through the prism of their multiple monarchy inheritance. Having succeeded Elizabeth I as England’s first Stuart king in 1603, James VI & I promoted a ‘union of hearts and minds’, hoping that the two formerly warring nations of England and Scotland might be peacefully reconciled within a new state, Great Britain. A new British coinage bore images of roses and thistles and a new flag design became known, eponymously, as the ‘Union Jack’. Accompanying the British vision of the new Stuart line was, moreover, a cosmopolitan range of dynastic, diplomatic and cultural attachments to the Continent. During the two years spent making the BBC films, the seeds of Devil-Land’s arguments were sown when reappraising the impact of Stuart rule in locations ranging from a windswept Aberdeenshire beach that once hosted an invading Jacobite force, to Derry’s city walls, Breda’s cobbled streets, Madrid’s monumental Plaza Mayor, Versailles’s Hall of Mirrors and the Vatican City tomb of the Jacobite ‘Old Pretender’. As I concluded, to many of their seventeenth-century English subjects, the Stuarts appeared an alien, imported dynasty that could not be securely relied upon to promote the national interest. And the distrust was mutual. Objecting to the rambunctiousness of the English Parliament to the Spanish ambassador in 1614, James VI & I admitted, ‘I am a stranger and found it here when I arrived, so that I am obliged to put up with what I cannot get rid of’. For her part, James’s Danish wife, Queen Anna, wrote in seven languages and after abandoning Lutheranism for Catholicism, became one of a succession of Catholic queens consort – Henrietta Maria, Catherine of Braganza and Mary of Modena – who all brought separate networks of political patronage, confessional attachments and foreign entanglements.

In emphasising themes of confusion, distrust and trepidation, rather than confidence, buoyancy and assurance, Devil-Land’s is a self-consciously subjective argument. But amid bitter confessional sectarianism across Continental Europe, the geopolitical stakes were high: between 1590 and 1690, the territorial extent of Protestantism was reduced from one-half to one-fifth of Europe’s landmass. Reviewing Devil-Land for The Sunday Times, John Adamson explained that ‘the reason for much of that century’s devilry, Jackson contends, comes from a single source: the question of England’s proper relation with Europe’. Since dynastic, diplomatic and economic decisions were invariably inflected by confessional choices, ‘get that wrong, and the nation would literally go to the Devil’. To foreign observers, seventeenth-century England frequently appeared infuriating: its political infrastructure was weak, its inhabitants capricious and its intentions impossible to fathom. Dispatched to London to congratulate James VI & I on his accession in 1603, the French diplomat, the count of Rosny, concluded that ‘no nation in Europe is more haughty and disdainful, nor more conceited in an opinion of its superior excellence’. In the 1630s, a Venetian envoy was informed by his Spanish counterpart, the count of Oñate, that ‘there was no school in the world where one could learn how to negotiate with the English.

More recently, ‘seeing ourselves as others see us’ formed the theme of an episode of Andrew Marr’s Start the Week Radio 4 programme last October, where parallels were drawn between Devil-Land’s arguments and Fintan O’Toole’s insightful history of Ireland since 1958, resonantly entitled We Don’t Know Ourselves. When populations of other countries were exhorted, between the late-1990s and 2008 ‘to be like Ireland’, O’Toole lamented that ‘our already hyped-up vision of ourselves was magnified by being reflected back at us in the admiring gaze of foreigners’. Coincidentally, this Start the Week discussion occurred weeks after a new entente discordiale had been reached in Franco-British relations, following Australia’s announcement of Aukus: a new three-way strategic defence alliance with the United States and Britain that required Australia to abandon a multi-billion dollar contract to purchase French submarines. For the first time in the history of the United States, France had recalled its ambassador from Washington, and had also broken off diplomatic relations with Canberra. But when asked why their counterpart in London had not been recalled, the French foreign minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, dismissed Britain as the redundant ‘fifth wheel on the carriage’. When it comes to trading insults, evidently not much has changed from 1638 when Louis XIV’s chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, ‘stated emphatically that, at present, England might be called the country where they talk of everything and conclude nothing’.

Clare Jackson’s Devil-Land. England under Siege 1588-1688 (2021) has been named as a ‘Book of the Year’ by The Times, the TLS, The Daily Telegraph and The New Statesman.