New Abstract Financial Value and Society in the Early Eighteenth Century

Funded by the Leverhulme Trust

The use of the term capitalism is so pervasive today, that trying to define what it means in practice might seem impossible. It is often now defined reductively by the degree of free market activity and individual property rights. But, like many ‘isms’ it took form in the late nineteenth century as a conceptual definition of a competitive economic organisation of society to counter socialist ideals of cooperative society. Although Marx only used the term capital, not capitalism, Marxists certainly subsequently adopted the term to refer to a system of cheap wage exploitation creating capital accumulation on the part of those who owned productive property. However, it is no accident the root ‘capital’ was used, and this derivation points us not towards market freedom, but rather towards a certain type of abstract value supported by an institutional structure involving the production of liquid paper instruments of credit which kept their value over time.

This project will investigate how these factors developed in early eighteenth century Britain. Even though the antecedents for such a system were laid in the banks developed much earlier in Italian cities such as Florence and Naples, by the late seventeenth century England had developed a comparatively well integrated national economy centred on London, which over the course of the eighteenth century would expand to include Scotland and Ireland into an Atlantic system. This allowed changes adopted there to become more embedded, and thus to have a more lasting effect. Through a process of public debate about the role of money and credit in the economy in the late seventeenth century, England manged to transform its relatively informal system of credit into one which combined informal flexibility with institutional accountability at a local level. This allowed the formation and use of capital to spread beyond merchants through the whole national economy. At almost the same time, Scotland pursued the same goals but followed a different path within a different legal system.

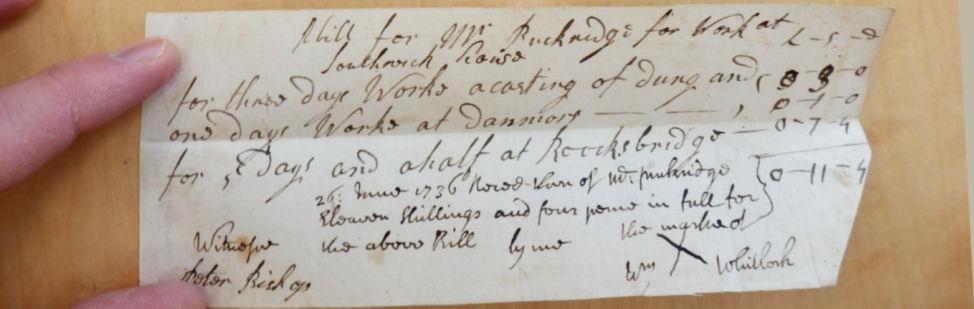

The well-known theory of the financial revolution has demonstrated how the stock market and a vast increase in new paper instruments of government debt created capital. But, equally important changes were happening in local society. On the security offered by an expansion of mortgaging, both farmers and regional tradesmen began issuing informal paper notes of hand and bills which could be used as currency to replace or augment previously much less secure oral credit. This was also made possible by a great expansion in the practice of accurate bookkeeping. In this way trust in currency was created from the bottom up, and a culture of credit was transformed into a culture of capital which needed to exist before capitalism of the nineteenth century could emerge. For its supporters it was defended as a means by which large sums could be invested in innovation and progress. For Marx, the key point about capitalist exploitation was that it was precisely the system which produced capital which allowed the capitalist to isolate himself and his family from any obligation to wage earners. It became only a wage relationship. But such a system did not originate in exploitation even if it ended there. The key theme of this study is that ‘capitalism’ is not just a set of institutions but a system of understanding and practice. The contestation of such practices came to shape and continue to shape our politics and morality. There were certainly contestations when capital emerged, but they were shaped around concepts like the metropolis vs the country, interest vs charity, the self and community, and the ethics of global production.