Pandemic Television: It’s a Sin and the Public History of HIV/AIDS in Britain

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is perhaps no surprise that a TV programme covering the history of a recent public health crisis has found an enthusiastic audience. I have been eagerly awaiting the release of Russell T. Davies’ new series ‘It’s a Sin’ because, just as my PhD dissertation does, it explores the HIV/AIDS epidemic and responses to it in England.

Broadcast to much fanfare, the series follows the lives of a group of gay men as they live through the HIV/AIDS epidemic in London. Many previous films have focused on the history of radical HIV/AIDS activist groups in America and continental Europe, with most looking especially to the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). The recent HBO series ‘Pose’ explored the emergence and early campaigns of ACT UP New York, while the 2017 film ‘120 BPM’ thrust ACT UP Paris into the international spotlight.

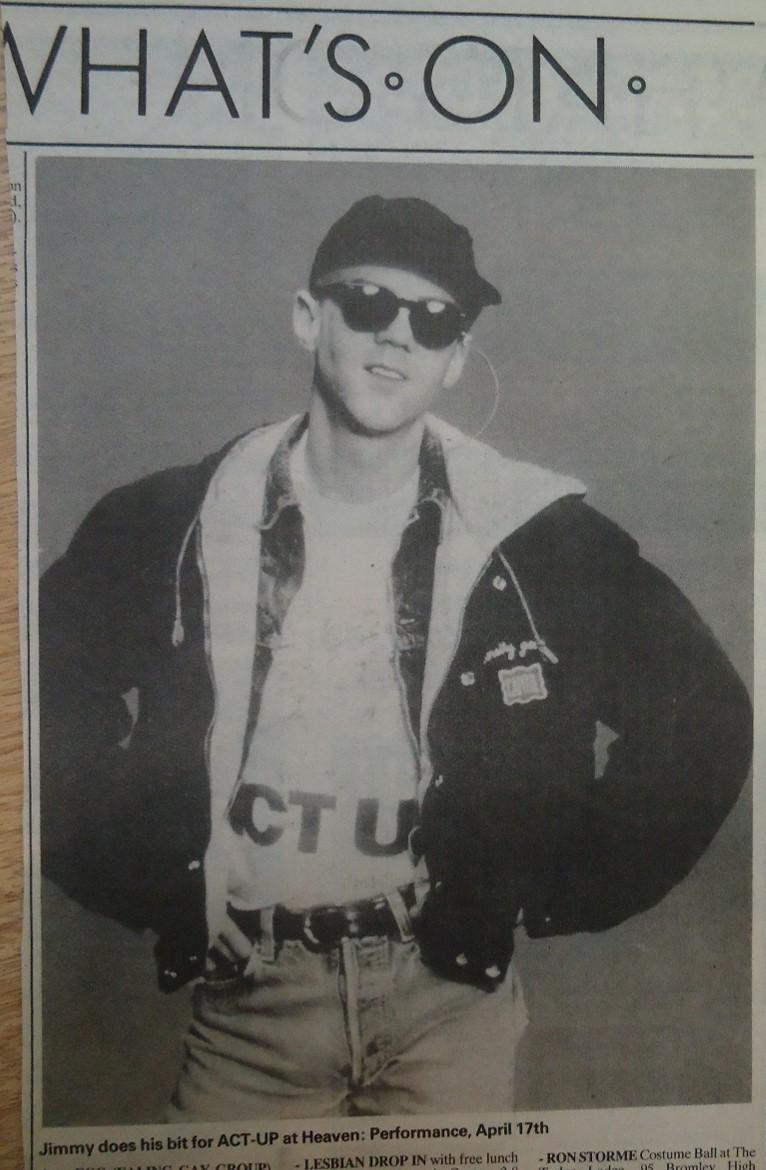

‘It’s a Sin’ is one of the first cultural productions to highlight the place of radical HIV/AIDS activism in the UK. Film, TV and historical accounts of HIV/AIDS activism have been quick to point to American examples, whilst historical accounts of the epidemic in Britain have downplayed the significance of such activists. The title of the series is taken from the Pet Shop Boys’ 1987 number one song of the same name, whose music video was directed by Derek Jarman, an English AIDS activist and filmmaker. They could just have easily drawn from the discography of Jimmy Somerville, lead singer of Bronski Beat and The Communards. Somerville was an early member of ACT UP London who was arrested several times on ACT UP demos and toured and performed to raise money for the group. As a solo artist in 1990 he released Read My Lips (Enough is Enough) in which he sang ‘Finding cures is not the only solution, and it's not a case of sinner absolution’. The song quickly became something of an ACT UP anthem, helped by the ‘ACT UP’ jumper worn by Somerville in the music video.

My PhD dissertation puts HIV/AIDS activists back into the history of the epidemic in England. England boasted several chapters of the international ACT UP Coalition. London was home to the first chapter, founded in 1989 off the back of the huge movement aimed at stopping Section 28 of the Local Government Act of 1988, which forbade the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ by local authorities. Soon after ACT UP chapters appeared in many British cities, including Edinburgh, Manchester, Leeds, Brighton and Norwich.

Capital Gay coverage of a Jimmy Somerville (pictured) performance to raise money for ACT UP in 1990.

Cambridge, which had a significant resistance movement to Section 28, also became home to an ACT UP chapter. It met on the last Sunday of every month in the City’s radical independent bookshop Grapevine, which operated out of the old Dales Brewery building on Gwydir Street, and which many readers may remember. ACT UP’s political reach extended to smaller provincial towns without active chapters of the group. An article in Solent Pride, a newsletter to mark Southampton’s 1992 gay pride celebrations, noted that ‘there are no ACT UP groups in Southampton, Portsmouth, Basingstoke, Reading, Aldershot, Bournemouth or Winchester’, but insisted that this did not ‘mean that we can’t be effective, in these, our hometowns’. ACT UP’s visible political presence in other British towns and cities was often the inspiration for people to become active in their local organisations or charities which formed part of the broader HIV/AIDS activist movement.

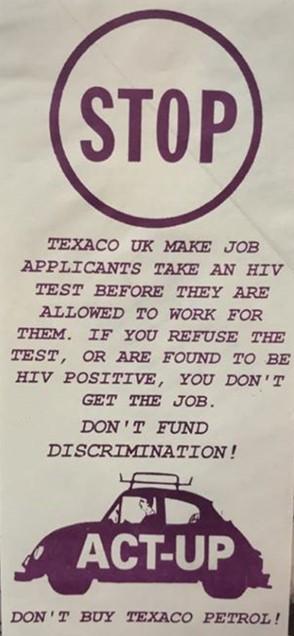

ACT UP was involved in several campaigns during its relatively short political life in Britain. Among the largest was directed against Texaco. The petroleum company had instituted a policy of mandatory HIV tests as part of their hiring process, refusing employment to those who tested positive. The policy caused outrage amongst AIDS activists across the country and largescale protests quickly followed. ACT UP Manchester began blockading Texaco petrol stations throughout the city, handing out literature to motorists explaining their actions and reporting largely sympathetic reactions in their newsletter. ACT UP ultimately failed to stop this policy, which ended up being reversed after HIV was listed as a named disability under the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, but they succeeded in bringing the issue into much sharper relief than might otherwise have been the case.

ACT UP leaflet, n.d., Norfolk Heritage Centre LGBT+ Collection Health and Wellbeing Box.

As ‘It’s a Sin’ demonstrates, radical AIDS activism in England was about visibility and public displays of resistance to a system which didn’t seem to be taking HIV/AIDS seriously. When the oral historian Wendy Rickard asked John Campbell, who had been a leading member of the group, to ‘say what ACT UP [London] was about’ in 1996, he replied: ‘It was about direct action, about going onto the streets and shouting very loudly and chaining yourself to whatever you could chain yourself to, kicking and screaming and everything to try and get people to take notice of AIDS’. We’re likely to see such displays in abundance on Channel 4 across the five episodes of the series. And whilst there is much more to the HIV/AIDS activist movement in England, as my research shows, seeing representations of the English chapters of this movement is something of a first for television, and has the potential to be informative and highly entertaining.

George Severs is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of History where he is writing up his PhD thesis on HIV/AIDS activism in England c. 1982-1997.