Constructing the university - Georgia Oman

History is written in buildings. By this I do not mean to state the obvious fact that most historians tend to avoid working en plein air, but rather that the shadow of the past can be felt within our built environment. As a PhD student, my own work explores the intersection of gender and physical space in British universities of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The ways in which buildings were designed and used in the past provides a lens through which to understand the wider social and cultural landscape of the societies in which they were produced. In the words of the writer John Gloag, ‘architecture is the most permanent and illuminating of unwritten records’.

My dissertation specifically looks at the ways in which attitudes towards the emergence of women as a new category of student during the second half of the nineteenth century shaped the physical fabric of the institutions to which they had so recently won admission. While the story of coeducation can be told as a tale of progress marked by the dates of pioneering ‘firsts’ achieved, such as women being admitted to courses and allowed to graduate, the narrative preserved within the material culture of buildings is more complicated, revealing as it does the difficulties inherent in translating the ideal of educational equality into practice.

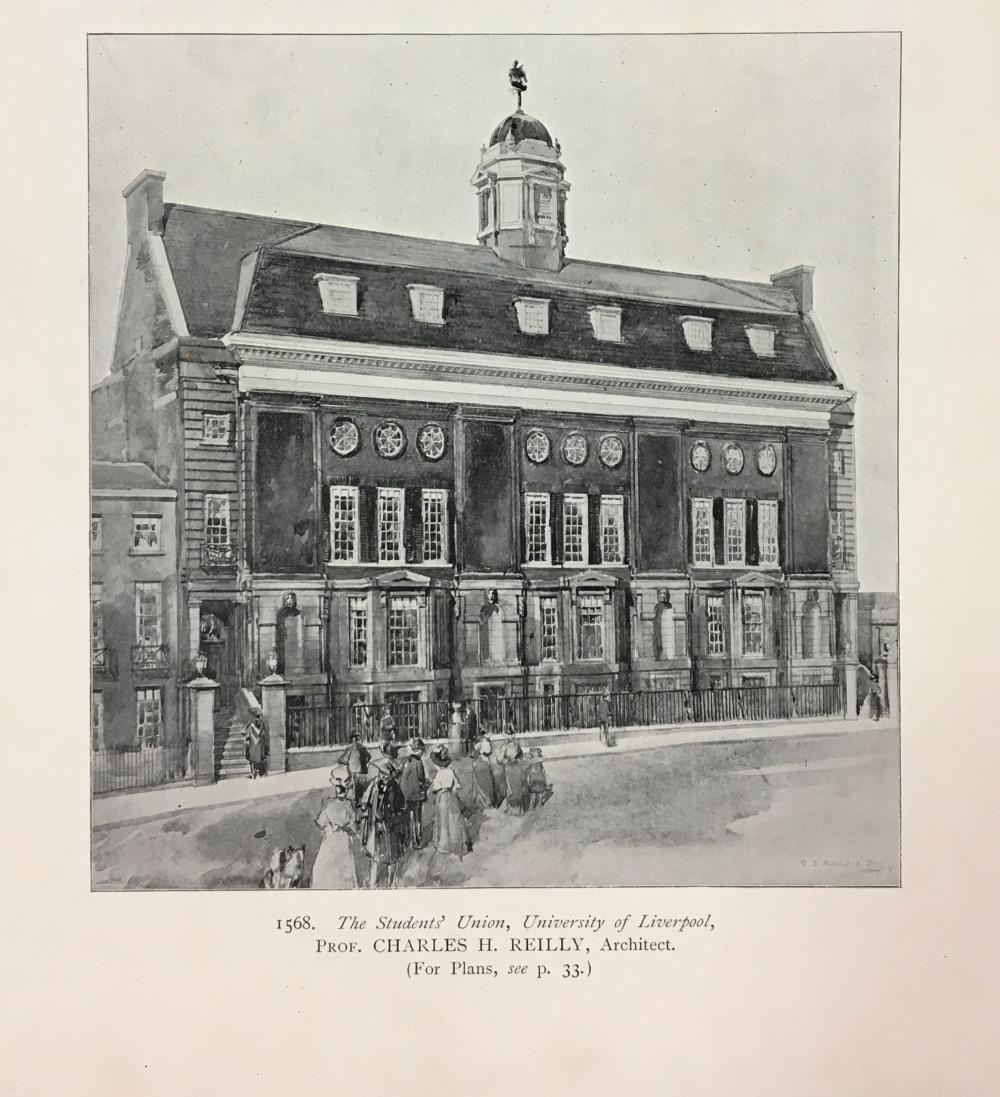

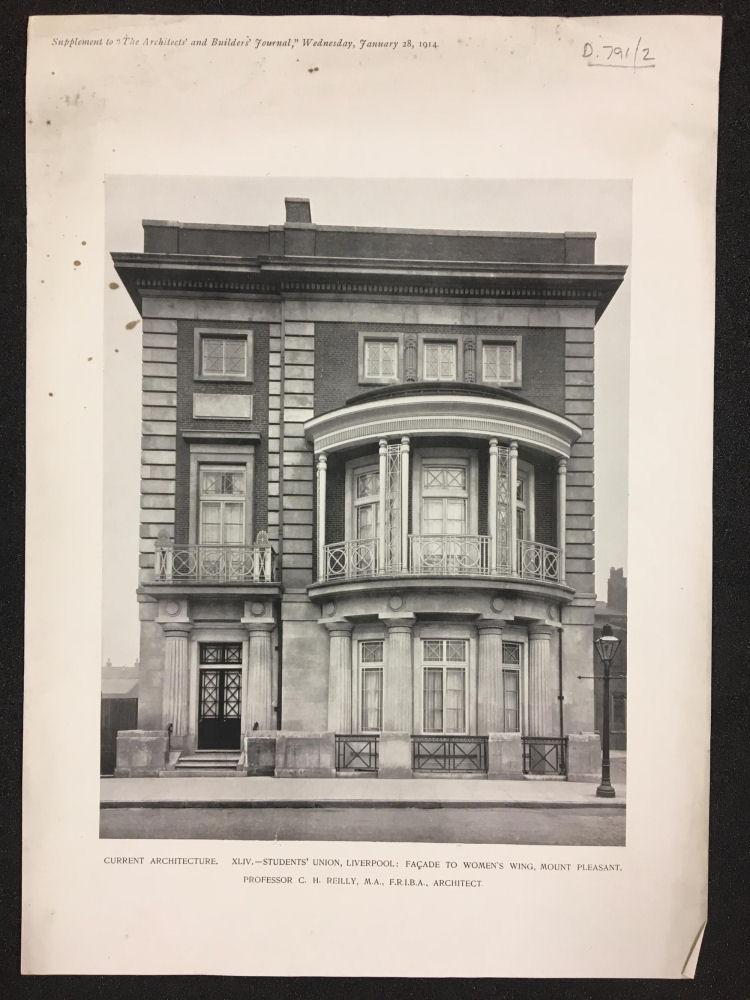

The two images below, for example, show the separate entrances to the University of Liverpool’s Students’ Union, a building envisioned as two distinct halves forming a complementary, yet separate, whole. With one wing of the building reserved for men and the other for women, entry to each section was even gained via different streets.

These explicit spatial divisions were further reinforced in an aesthetic sense, with the architectural style of each façade chosen to reflect the innate gender distinctions of the building, typified in this case by masculine Baroque and feminine Regency.

Being able to undertake this research while studying as a postgraduate student at Cambridge has been an immensely rewarding experience. As well as the obvious access to the facilities, knowledge, and support provided by the University, being able to study academic buildings while being surrounded by some of the most spectacular examples of educational architecture in Britain – from the Gothic splendour of King’s College Chapel through to the postwar modernism of James Stirling’s History Faculty building – has provided its own ineffable benefit. If history is written in buildings, then I can only hope that my own historical offering captures some small part of the buildings in which it was written.

NOTES:

- Gloag, John, The Architectural Interpretation of History (London: A & C Black, 1975).

- ‘The Students’ Union, University of Liverpool, Prof. Charles H. Reilly, Architect’, Academy Architecture, 1907II. – London (p. 32), D207/1/1/(ii), University of Liverpool.

- ‘Current Architecture. XLIV. – Students’ Union, Liverpool: Façade to Women’s Wing, Mount Pleasant. Professor C. H. Reilly, M.A., F.R.I.B.A. Architect’, Supplement to “The Architects’ And Builders’ Journal,” Wednesday, January 28, 1914, D.791/2, University of Liverpool.