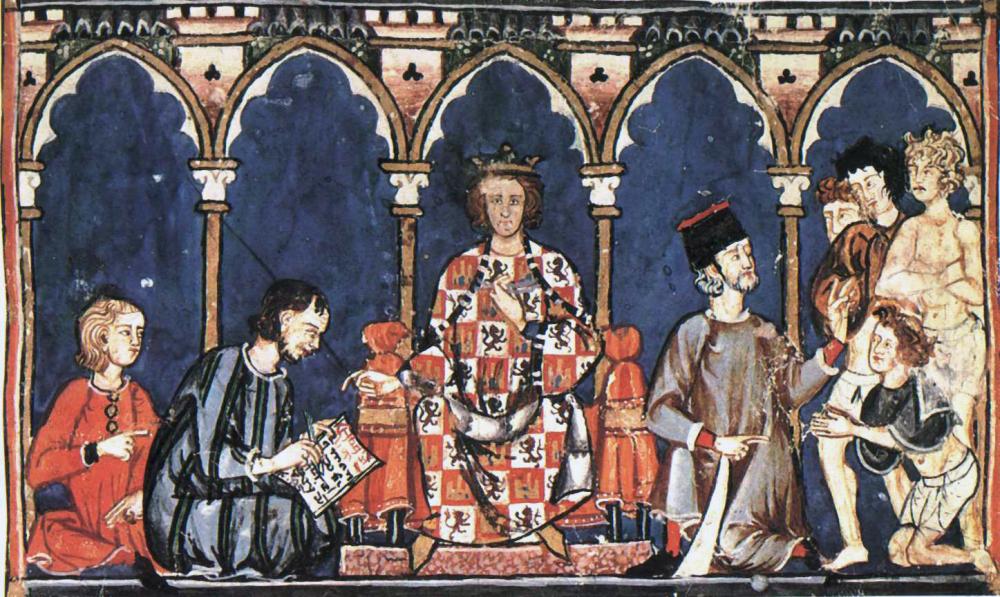

Jews At Court in Medieval Spain, 1000-1300 CE

Between 1000 and 1300, Iberian Christian polities rapidly expanded over Islamic lands in the so-called ‘Reconquest’ of al-Andalus. This expansion resulted in the forced coexistence between neighbours of different faith groups in abruptly formed ‘frontier societies’. This forced cohabitation, a process better known as convivencia, led in consequence to the emergence of pressing questions about how new subject Jewish and Muslim communities were to be accommodated under the new Christian rule. The exceptional socio-political conditions of the Iberian medieval frontier enabled the participation of Jews and Muslims in creating complex systems of legal pluralism in these newly-conquered societies.

Historiography has tended to depict such inter-religious interactions in terms of violent Christian Reconquest or of irenic coexistence, better known as convivencia. Instead, this project advances a multi-layered view of these interactions, that considers the socio-economic agency of these communities, without forgetting the religious, cultural and ideological specificities of each faith group.

Focusing on records of Jewish involvement in Christian courts of law, this project observes members of this religious faith group as litigants, defendants and witnesses in a range of processes related to penal, fiscal and economic disputes. These disputes involved participants from a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds, pitting plaintiffs against Christians, Muslims and other members of the Jewish community. In sum, these records reveal the position of Jewish petitioners in medieval Castile, Navarre and Aragon as cultural, economic, and social brokers. They enable the current project to approach Jewish participants in secular courts of law as ‘the consumers of the law’, in the words of D.L. Smail, examining their investment in the procedural apparatus of central and late medieval justice.

This project shifts focus from the written law – in which legal boundaries between Jews, Muslims and Christians were more neatly demarcated – to evidence of inter-religious judicial praxis. Court records offer a perspective not of those who designed the courts, but those who invested in them.

A Case Study of Jewish-Christian Judicial Entanglement: Abraham of Tudela

Consider the experiences of plaintiffs such as Abraham of Tudela: this was a resident of Barcelona who in January 1285 CE repudiated the legal authority of the local Jewish community. Instead of litigating through the ordinary halakhic court available to local Jews, Abraham resorted to the secular judiciary of the kings of Aragon. This Jewish plaintiff would duly receive a guarantee from monarch Pere II (r. 1276-1285) that firmly protected him and his family from any judicial impositions by the Jewish community of Barcelona, including security from Jewish communal bans (shamta and herem) and freedom from all local Jewish statutes (takkanah).[1] Cases such as these led Jonathan Ray to conclude that Jewish communities ‘exhibited a willingness to use any institutions that would benefit them personally, regardless of whether they were Jewish or Christian’.[2] Jews appear to have used whatever courts were available to them, even in the face of halakhic rulings against the use of Christian courts of appeal.[3] The project seeks to test whether this logic was at work throughout Iberia.

As Abraham’s example vividly suggests, however, the key question is not whether these records reveal Jewish ‘agency’. Instead, the project asks what happened when Jewish individuals chose to use gentile courts instead of intra-community legal structures. I will describe how, in navigating the legal systems at their disposal, Jews such as Abraham recognised Christian power, and put Jewish justice in competition with Christian courts. Abraham’s direct confrontation with the local Jewish communal authorities confirms that judicial experiences in medieval Iberia transformed both the dynamics of Jewish-Christian entanglement and the nature and composition of Iberian Jewish communities themselves.

[1] ‘Absoluentes, uos eet bona uestra, ab omnni alatma, tacana, hirem et ab omni alio uetamento seu ligamento per judeos Barcelona contra uos factis...’ Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó (ACA), Barcelona, Reg. 13, f. 275. cf. Navarra Judaica Vol. I, doc. 84, p. 82. For more examples from this period, see Klein, Jews, Christian Society and Royal Power, pp. 154-161.

[2] Ray, ‘The reconquista and the Jews: 1212 from the perspective of Jewish history’, Journal of Medieval History 40 (2014), p.165.

[3] Yom Tov Assis, ‘Yehudei Sefarad be-Arkaot ha-Goyim’, in Menahem Ben Sasson et al. (eds.) Tarbut ve-hevrah be-toldot Yisra'el bi-Yemei ha-Beinayim: Kovets Ma'amarim le-Zikhro shel Hayyim Hillel Ben-Sasson (Jerusalem, 1989), pp.399–430.

Main image: Alfonso X of Castile and his court, Libro de los Juegos (Book of Games), c. 1285. From Wikimedia Creative Commons

Second image: Moses and Aaron come before the Pharaoh. Golden Haggadah, c. 1320 CE, Catalonia. From the British Library manuscript collection