Genealogy, slavery and the digital archive

Malik Al Nasir

It’s not every day you turn on your TV and see someone who looks almost exactly like you, especially when they were born in 1856. However, that’s what happened to me in 2002, when a documentary aired on the world’s first black international footballer—Andrew Watson—who’d captained the Scottish national football team in the 1880s. He came from the same part of what was then British Guiana as my father, had the same surname, and the likeness to me was uncanny. That’s when I resolved to find my ancestral roots. The search would bring me to an important archive and eventually to Cambridge.

Andrew Watson (1856-1921), the world’s first black international footballer.

My father Reginald Wilcox Watson was born in 1918 in British Guiana. He’d gone to sea in 1935, then settled in England and started a family in the 1960s. He’d often said, ‘One day I’m going to take you back home to the sugar cane,’ though he never did. He died when I was a teen. The Guiana he’d left was a plantation-based colony that produced much of Britain’s sugar. European merchants owned the plantations, worked first by enslaved Africans and later by Indian and Chinese indentured labourers. To understand my ties to this history, I began scouring the archives, starting with my grandfather, schoolmaster George Edward Watson, born one or two generations removed from slavery.

I’d drawn a blank on the Demerara connections having started a family tree in 2002, so in 2008 I travelled to the now independent Republic of Guyana to learn more about Watson. I spent a week there with a fellow researcher from New York, Dr. Tonya Leslie, who searched archives in Georgetown for all things ‘Watson’ whilst I took a series of field trips to find living relatives. Armed only with the names of my grandparents and little else, I discovered a cousin in D’Edward village in Rosignol, Berbice.

I’d also discovered that Andrew Watson’s father, Peter Miller Watson, owned at least two plantations in Demerara and his wider family owned many more. His father, James Watson, was the Chamberlain for Lord Dundas – the Earl of Orkney. Peter had travelled out to Demerara with two brothers to manage the family estates as a young man in the 1820s, during slavery. Like many Scots, the Watson brothers left their black progeny to inherit lands, endowments and annuities from their estates. Peter Miller Watson’s heirs included his son, Andrew Watson, and his daughter, Annetta. His brother, William Robertson Watson, similarly bequeathed plantation land to his black children, land that passed down to my grandfather and cousin in D’Edward village. The land in Berbice that my cousin now lived on, it turned out, was the key to unlocking my connection to Andrew Watson: we are distant cousins, related through a Scottish slave-trading family.

As I deciphered these connections, a broader story started to emerge. Peter Miller Watson had come into ownership of two plantations in his own right, but as a descendant of George Robertson, he managed many more. A partnership founded by a group of Scottish sugar and slave merchants led by Robertson and later joined by Samuel Sandbach in Grenada relocated to Demerara after Fédon’s slave uprising of 1795. After the Dutch ceded Demerara to England in 1813, Dutchman Phillip Frederick Tinne joined the firm that became known as Sandbach Tinne & Co. The group reportedly prided themselves on trade in ‘Demerara sugar, molasses, rum and prime Gold Coast negros’ (J Rodway, 'History of British Guiana', 1893).

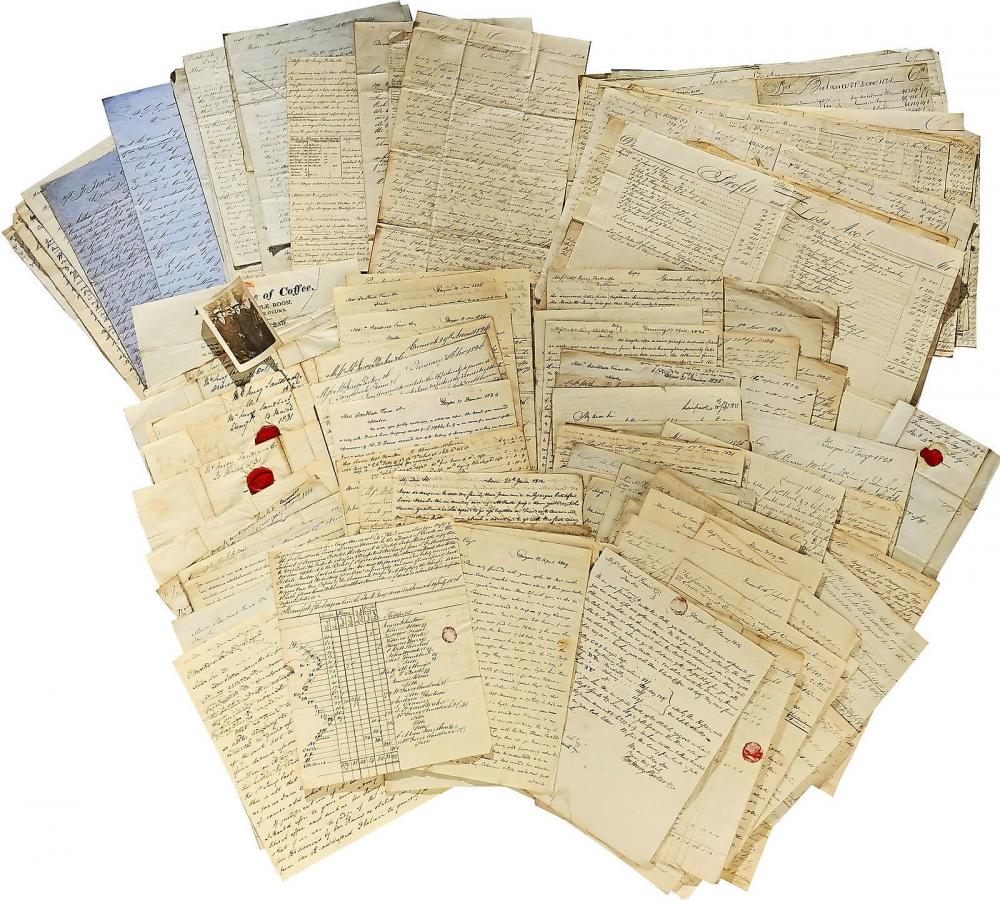

As I searched for more documents to fill out the story, a nineteenth-century archive containing over 100 letters written by Samuel Sandbach, his partners and Andrew Watson’s father came up for sale, along with complete accounts of the Sandbach Tinne Co. and its affiliates from 1790 to 1880. I bought it without hesitation. After fifteen years of study, I had never seen a more complete account of any major slave trader. The collection detailed just how influential, rich, and politically connected they were.

Among other things, the archive showed that Charles S. Parker, one of Sandbach Tinne Co.’s founders, ran the Glasgow side of what became Sandbach Tinne, whilst Peter Miller Watson ran the Demerara operation. Parker commissioned the construction of their fleet of slave ships, later repurposed to carry indentured labourers from Calcutta and Shanghai to the cane fields of Demerara and Berbice for a lifetime of harsh servitude under the management of Peter Miller Watson, the slave trader from whose mother – Christian Robertson Watson – I myself descend. Beyond this, it reveals a sprawling family’s commercial and banking network sharing in and processing the proceeds of enslavement.

Part of Malik Al Nasir’s Sandbach Tinne slavery archive, 1808-1880

In 2017 I’d presented some of my artefacts and preliminary research findings at the University of Cambridge, at a seminar called ‘Artists as Activists’ exploring how I’d used poetry to reassert my cultural identity, which had been obscured by colonialism and slavery. When Dr Hank Gonzales heard about my archive, he invited me to apply to Cambridge to study it for a History PhD. After the story of my archive hit the national and international press, I was awarded a full ESRC studentship from Cambridge DTP and matriculated at St Catharine’s College in 2020. With Sandbach Tinne as a case study, I am using my archive to study the economic impact that the Guiana sugar and trade in enslaved Africans had on the financing of the wider trans-Atlantic slave economy and on the industrial revolution more broadly.

To truly dig into this unique slavery archive, I needed some help from the experts. In 2021, I approached Cambridge Digital Humanities to have my archive digitised and catalogued, as well as have all the folios transcribed. This would produce a unique primary dataset of the slave traders who were both my ancestors and the owners of my ancestors. With a discretionary award from the ESRC DTP and the support of Dr Mark Purcell and Huw Jones, I have partnered with the University Library to turn the archive into a collection on the Cambridge Digital Library platform. I was honoured to have been made an ‘Associate’ of Cambridge Digital Humanities in the process. I’m also writing a book on the subject entitled ‘Searching for my Slave Roots’ (Harper Collins), due for publication in 2023.

It has been an incredible journey, where a desire to find my ancestral roots has led to my PhD research at Cambridge, a book deal with a major publisher and filming with BBC Scotland for the definitive documentary on Andrew Watson, the World first black international footballer. The programme aired earlier this year. It’s ironic that what started with a documentary about Andrew Watson ended with a documentary about him.

Malik Al Nasir (right) and footballer Mark Walters (left) (BBC Scotland film shoot - Andrew Watson’s Grave).