(viii) Imagining Ancient Rome in film, television and popular culture

To consider ancient Rome on film is to discover that a familiar iconographic history of bad emperors, gladiators, soldiers, spectacles and dangerous women has persisted unchanged to an extraordinary degree despite huge transformations in technology, publics, and media since the mid-nineteenth-century. This option asks how such a collectively-held popular ‘history’ intersects with and mutually influences the concerns of professional historians. How should we approach such films as sources for historical attitudes and values?

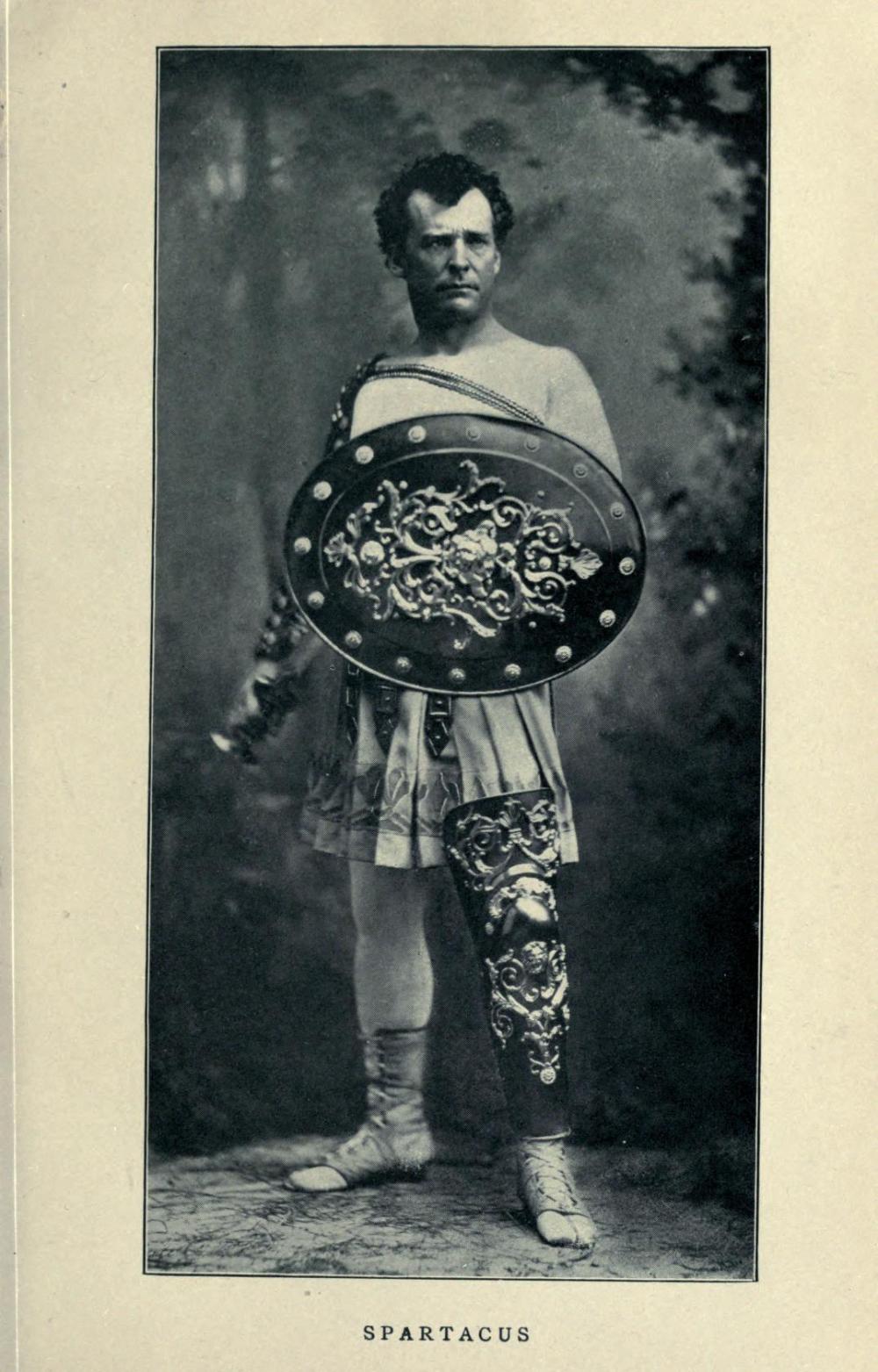

The course pays specific attention to the role of the relatively brief Hollywood studio era in transmitting nineteenth-century cultural repertoires into the global and digital twenty-first century. It begins by investigating the stereotypes of ancient Rome in nineteenth-century theatre, painting and fiction drawn on by early silent film (1890s-1920s); considers how these images became dominant via Hollywood cinema (c. 1930s-50s); looks at how that dominance was challenged in the 1960s (parody, independent/auteur films) and lastly how they have been revived in the digital present, where recognisability is a key commodity. On the way, we will notice how contests about authenticity, accuracy and truth have often worked to sustain, rather than critique, these familiar tropes; and how humour, parody and subversion have usefully directed attention to the nature of all ‘history’ as selection, narrative, and audience-specific.

By the end, students will understand each film studied as situated in this overall wider context of influences and impact; will be familiar with the various fundamentally distinct historical social phenomena that ‘film’ has been in different times and places; will view any act of cultural production as embodying multiple, and usually contradictory simultaneous agendas (including any stated interest in ideas of the factual, authentic, or historical); and will understand that the many available meanings of all artistic sources depend on the various subject positions from which they were (and are now) viewed.

A cinematic Rome is by definition a mass phenomenon. Film has always been expensive, so it is not surprising that its products - precedent-driven and risk-averse – address themselves to what they assume is a pre-existing popular image, or familiarity. This collectively-held imaginary Rome becomes a ‘traditional history’, and is understood as such by its makers and audiences: it operates analogically, as an ongoing resource for talking about the nature of the present. Whether Italian nationalism, American depression-era Christian proselytising, wartime propaganda, or post-colonial rebellion, films about ancient Rome have been particularly understood as parables about now, rather than then; us, rather than them. Rome is a site where otherness is expected to be played out: dictatorship and the world wars, women and orientalism, immorality and religion. It has been a key way to talk about empire, nationalism, ethnicity, class, gender - and as perennially associated with scale, spectacle, and excess the entertainment business itself. So it is a self-referential lens through which to introduce the history of film.

This material is intended for current students but will be interesting to prospective students. It is indicative only.