Making sense of sickness in medieval and early modern England - Philippa Carter (Trinity Hall)

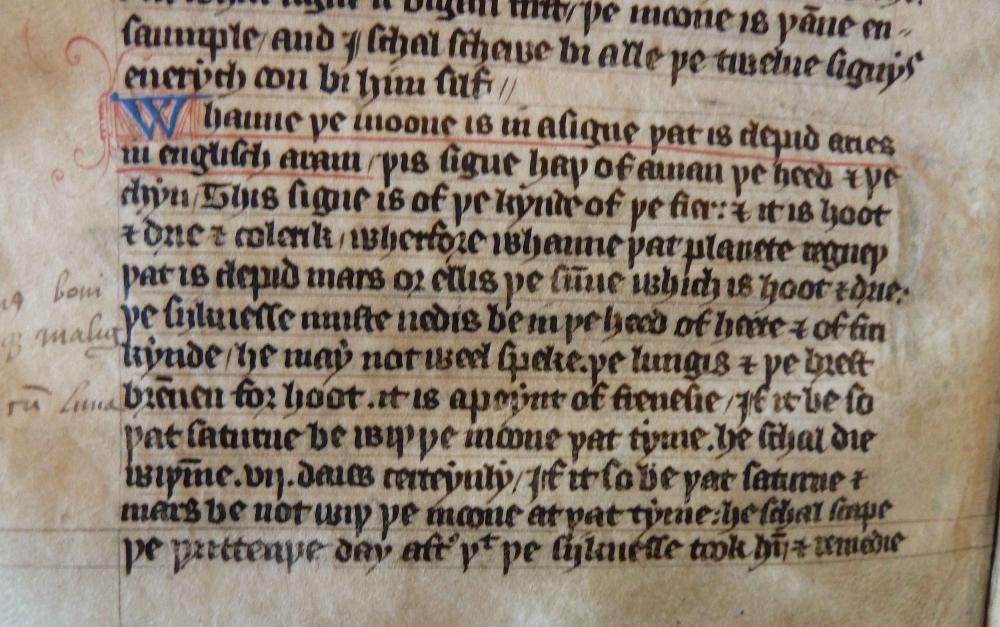

‘When the moon in a signe called Aries, in English, a ram, this signe hath of a man the heed & the chin… it is a point of frenesie” ‘The Boke of Ypocras’, Cambridge, Gonville and Caius MS 336/725, f.102v.

When I began my PhD in Michaelmas 2017, I did not picture myself spending long afternoons reading horoscopes. My thesis, I had decided, would look at ‘frenzy’, a disease state which was observed, discussed, suffered, and treated across Europe and the Middle East from antiquity long into the early modern era. I wanted to explore how understandings of the disease changed in England before, during and after the religious reformations of the sixteenth century. By the close of the century, medical theory had remained relatively stable, but large swathes of common knowledge about human nature, the cosmos, and the supernatural had been dismantled or refashioned. Frenzy offers a vantage point onto this landscape of flux and continuity, precisely because it was thought to affect almost every part of the sufferer: the brain, the body, the mind, the memory, the emotions, and the soul. A study of one disease – now defunct, once very real – channels some of the turbulent intellectual, social, and cultural currents which transformed English society during this period.

Trying to gain a sense of the frameworks with which medical practitioners made sense of disease, I have been on the hunt for texts which they owned, copied, wrote, or annotated. This search brought me to the library of Gonville and Caius college, where I was lucky enough to be able to study the manuscript shown here. It also brought me, unexpectedly, to astrology. Doctors in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century England, like today, were expected to be able to read their patient’s body for signs of disease. Unlike today, they were also expected to be able to do the same for the patient’s astrological chart.

Credit: Gonville and Caius library

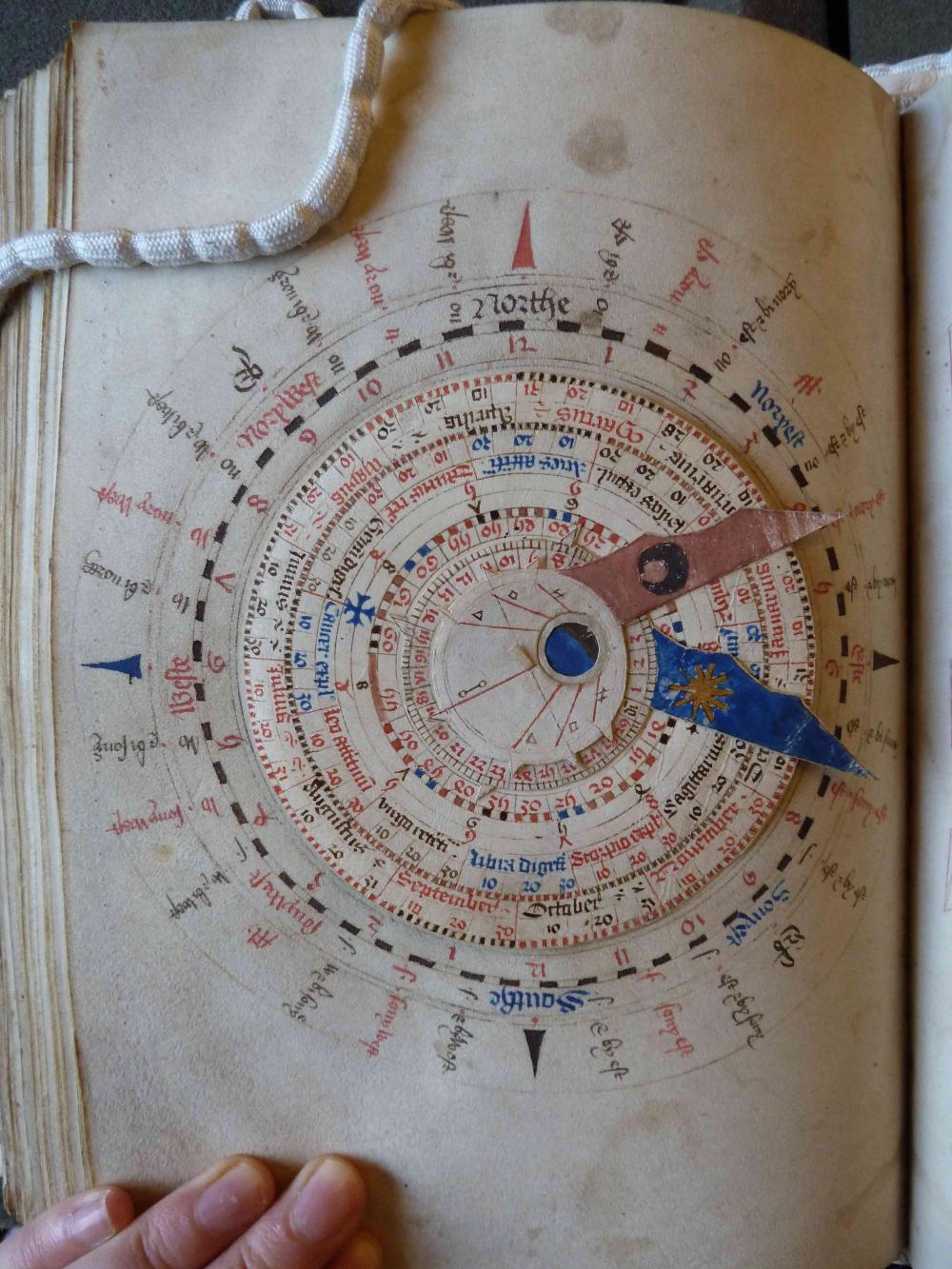

A ‘volvelle’, a paper tool for working out astrological alignments. Gonville and Caius MS 336/725, f.158v.

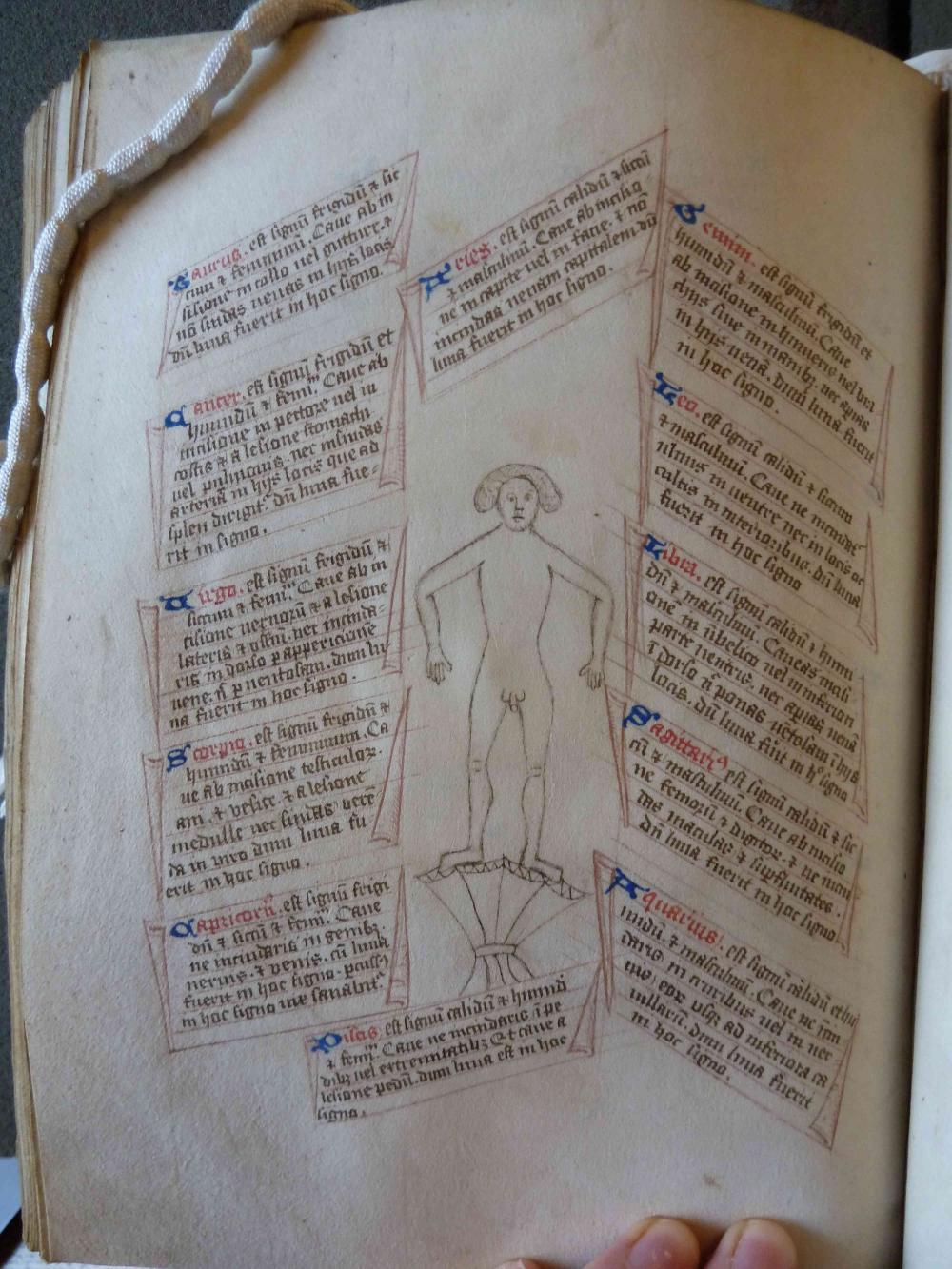

This fifteenth-century medical compendium is far too large, expensively decorated, and well-preserved to have ever been carried around by a physician at his belt. Yet it contains many of the texts and images about astrological medicine which circulated widely in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century England. One such text was the ‘Boke of Ypocras’, excerpted above. Thought (wrongly) to be by the ancient medical authority Hippocrates, it urged physicians diagnosing the sick to locate the position of the moon within the twelve constellations of the Zodiac. Each zodiac sign possessed a particular sway over the earthly phenomena which partook of its qualities: the seasons, the elements (air, fire, earth, and water), the life-cycle, and the human body. You can see these correspondences mapped out on the body of the manuscript’s (faintly dismayed) ‘zodiac man’ (left).

Credit: Gonville and Caius library

‘Zodiac Man’, Gonville and Caius MS 336/725, f.159v.

Aries was the first constellation to rise on the eastern horizon in the morning, and therefore exercised its influence on the foremost part of the body, the head. Like the sun with which it rose, it was a hot, dry, fiery sign. Frenzy was caused by a hot, dry, burning inflammation in the brain. If the moon was passing through Aries, this was a moment in which the patient was especially vulnerable to the disease: it was ‘a point of frenesie’.

Early medicine can seem outlandish at first glimpse, but my research this year has left me admiring the sophisticated and satisfying ways in which it wove diverse natural phenomena into an intelligible whole. Two aspects of the research environment at Cambridge have been especially rewarding. The first has been the immense richness and range of the sources to which historians have access, at both the University Library and the college libraries. The second has been the chance to be a part of the research communities of both the History Faculty and the History and Philosophy of Science Department. If I have grown as a historian since coming to Cambridge, it is a result of the many challenges, questions, tips, comments, and encouragements I have received in both of these environments.

Images printed by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.